By nearly a 2-1 margin, an unprecedented number of Americans believe the nation needs a third major political party, compared to those who are satisfied with the Democrats or Republicans.

A largely overlooked Gallup poll conducted a few weeks ago found that 61 percent of voters favor the creation of a legitimate third party. That is the highest level of support in Gallup polling history.

Barely a third of those questioned, 34 percent, said the duopoly of the Republican and Democratic parties suffices. That figure perhaps reflects the electorate’s anxiety in 2017 more than any other data point.

The new numbers indicate a trend of increasing third party support that accelerated in 2013. Much of the backing for this monumental change in American politics comes from independents and centrists, as the polarization and gridlock on Capitol Hill has prompted extraordinarily low approval ratings for Congress.

Polling by Gallup and Pew Research has consistently shown that independents represent the largest voting bloc in the U.S., much larger than either Democrats or Republicans, as their numbers have hovered around 40 percent since 2010.

The numbers also suggest that a solid majority of partisans view the party they support – or lean toward — as either not pure enough, or too dogmatic. As a result, backing for a third party is seeping into the ranks of Democrats and Republicans.

At the same time that the GOP controls the White House and Congress, Gallup found that 49 percent of Republicans think a third major party is needed, while 46 percent say the two-party system is adequate. The split is similar among Democrats: 52 percent like the idea of a third party, while 45 percent prefer the existing structure. However, a whopping 77 percent of independents favor having a third major party, while just 17 percent think the Democratic and Republican parties are sufficient.

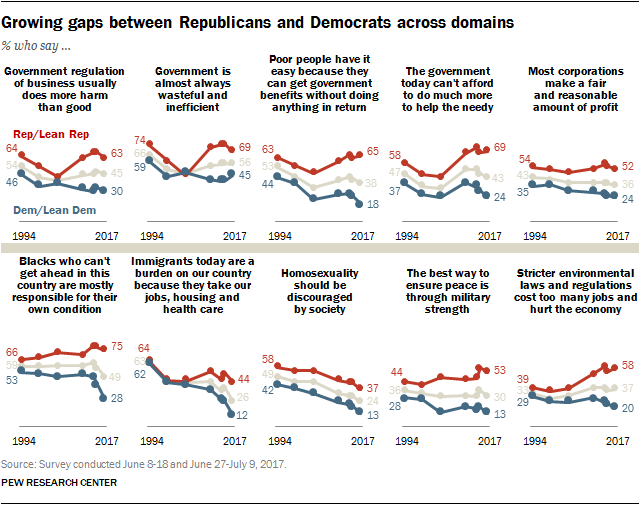

Meanwhile, a new Pew study documents a massive split among die-hard Democrats and Republicans that has left a huge gap in the middle consisting of moderates and independents. Pew found that self-identified Republicans and Democrats have never been further away from each other in terms of their ideological views of the world.

At a rapid rate, both parties have become increasingly hyper-partisan and homogeneous in their beliefs, meaning that compromise and pragmatism are not on their agenda. (The graph at the bottom of this page, with independent voters’ views in gray, shows just how divided the nation is on basic issues.)

Consider this: As recently as 1994, more than one-third of Republicans were identified as more liberal than the average Democrat. That number is 5 percent today. Same with the Democratic Party, where 30 percent were more conservative than the average Republican in 1994 while just 3 percent are today.

Heterodoxy no longer exists on the left or the right and the result is that Congress’ approval rating stands at a lowly 16 percent, even among Republicans.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that some Republicans lining up early to run for Congress are operating on the theme that the GOP-controlled House and Senate is fully dysfunctional.

It should be noted that this polling does not indicate a wave of post-2016 support for minor parties nor for presidential candidates such as the Green Party’s Jill Stein or the Libertarian Party’s Gary Johnson, both of whom, in retrospect, served the role of clownish outsider candidates on the fringes.

Lydia Saad of Gallup offers a lay of the land:

At various points since 2007, a majority of Americans have contended that a third major political party is needed in the U.S., while the minority have believed the two major parties adequately represent the American people. That pattern continues today with an unprecedented five-year stretch when demand for a third major party has been 57 percent or higher, including 71 percent or higher among independents.

While this may seem promising for any group thinking about promoting such a party, it is one thing to say a third major party is needed and quite another to be willing to join or support it. Americans’ backing of the idea could fall under a mentality of “the more, the merrier,” in which they would be pleased to have more viable political choices even if they vote mainly for candidates from the two major parties. And that says nothing of the structural barriers third parties face in trying to get on the ballot.

With most Republicans and Democrats viewing their own party favorably, the real constituency for a third party is likely to be political independents, meaning the party would have to be politically centrist. Thus far, the Green and Libertarian parties have succeeded in running national presidential campaigns but not in attracting big numbers of registered members. But with record numbers of Americans frustrated with the way the nation is being governed, the country could be inching closer to having enough people who want an alternative to the status quo to make it a reality, at least with the right candidate at the helm.

One caution: Political observers tend to wrongly associate talk of a third party with future presidential campaigns. This giddiness was on full display this past summer when Republican Ohio Gov. John Kasich, the most moderate candidate in the 2016 presidential election, announced that he would be working on key issues with a fellow pragmatist, Democratic Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper. The Washington Beltway media immediately, and inaccurately, speculated that a Kasich-Hickenlooper presidential ticket was in the works for 2020.

Beyond the unfair barriers to ballot access, a popular independent party ticket would face the immovable force of the Electoral College. If the electoral votes were substantially split three ways, the House would decide the presidency, and independent outsiders would have no chance in that cliquish atmosphere.

The only way a third party could succeed is with a bottom-up approach, establishing state legislators, governors and members of Congress as part of an emerging independent/centrist party. The presidency will have to wait.