By Chad Selweski

For Bridge Magazine

When she was in her 40s, Jolene Mcclellan worked full-time at a retail store and rode motorcycles and pedaled bikes in her spare time.

Three back surgeries later – and with cerebral palsy symptoms worsening – Mcclellan is disabled, relying on a wheelchair and living with constant pain throughout much of her body.

Now nearly 60, she said she hopes to supplement her monthly disability checks by landing a part-time job, maybe answering phones or doing computer work, though she has no use of her right hand from her cerebral palsy – and the recent onset of multiple sclerosis.

“I never knew I was going to get to this point. I never expected it. Not at my age. Not at 59,” Mcclellan said. Her last job, nearly 15 years ago, meant working on her feet for eight hours despite a metal brace on her right foot. “I know people who are 80 who get along better than I do.”

Mcclellan lives in the tiny village of Kingsley, north of Cadillac, on the fringe of an area known darkly as Michigan’s “Disability Belt.”

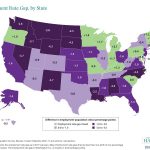

It’s a label most commonly applied to a wide swath of workers extending from the Deep South up through Appalachia. It signifies a region where post-recession aging workers in poor health and with few prospects for work have turned to federal disability benefits as a last resort, a replacement income for their long-lost unemployment checks.

Less well known is that an area consisting of 17 northern Michigan counties – mostly in the upper Lower Peninsula – qualifies as a separate strand of this Disability Belt, with economic distress nearly as overwhelming as in rural sections of Arkansas, Alabama and West Virginia.

Across this region, an area plagued by persistent unemployment and poverty, a surprising number of desperate workers have turned to Social Security disability benefits to earn a livelihood. Many don’t expect to return to the job market – unless federal investigators throw them off disability rolls.

In some counties, rates of poverty and disability hover around 15 to 20 percent, raising questions about whether a some portion of working-age residents apply for disability as much from despair that they will ever land another job as from physical necessity.

Advocates for the disabled say that is not the case, noting strict eligibility requirements for federal assistance and the fact that most applicants for disability are rejected. But that view is not unanimous.

One of the nation’s leading experts on the disability program, economist David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, argues that medical advances and improved equipment that can help the disabled return to the workforce are ignored by the Social Security system.

David Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is a leading researcher and critic of the current system for disability insurance.

“Social Security Disability Insurance is ineffective in assisting workers with disabilities to reach their employment potential or maintain economic self-sufficiency,” Autor noted in a report he co-wrote in 2010. “Instead, the program provides strong incentives to applicants and beneficiaries to remain permanently out of the labor force.”

Northern Michigan is part of a national phenomenon that emerged two decades ago and especially during the Great Recession of 2008-10, when an abrupt decline in blue-collar jobs left certain workers – mostly in their 50s, suffering from chronic medical conditions – unemployed or underemployed for years at a time.

They dealt with persistent pain, often job-induced, and eventually found themselves unable to lift heavy items, stand for hours at a time, or even efficiently climb stairs.

With jobs in manufacturing, construction and similar manual labor beyond their reach, these economic outcasts also held little chance of landing employment in the region’s fragile retail sector or service industries. Armed with a high school diploma or less, they were unlikely to find office work.

So, they turned to the Social Security system’s disability insurance.

Continue reading here.

Photo: John Russell/Bridge Magazine