As the Washington Beltway tries to shift from health care reform to tax reform, one provision that would limit the home mortgage deduction could have a surprising outcome across the country and particularly hurt homeowners in three Michigan counties.

Oakland, Washtenaw and Livingston counties could see their mortgage interest deductions, which now average more than $2,000 on IRS tax forms, largely disappear. They rank among a select group of counties nationwide that have a lot to lose from Trump administration plans to substantially limit the deduction.

Conventional thinking would place Oakland and Washtenaw in this select group because of their large homes and substantial household incomes. Livingston seems to consistently fly below the media radar as a county with substantial growth, increasing wealth and rising home prices.

But the effects of this mortgage deduction plan vary widely across U.S. geography in ways that confound conventional wisdom, according to the Tax Foundation research group.

The counties who would be hit hardest unsurprisingly include the East and West coasts. Numerous California seaside counties are on the list, and all of the counties in the wealthy Washington suburbs would be tagged by this tax change. In Loudoun County (northern Virginia) taxpayers can take an average home mortgage deduction of $6,365 – highest in the nation.

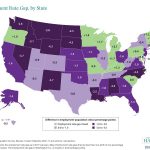

Yet, state-by-state and county-by-county Tax Foundation maps show that states such as Texas and Florida enjoy only modest benefits from the mortgage deduction while many counties in the Rocky Mountain West, including those in Idaho and Montana, have profited handsomely from the deduction.

Although the details on the Trump administration’s tax reform proposal remain infuriatingly vague, reports indicate that the Trump administration, in exchange for a higher standard deduction, may reduce the cap on the home mortgage interest deduction from a maximum of $1 million debt to $500,000. That provision could raise as much as $95 billion to $300 billion over the next decade, depending on how the cap is structured.

The tax increase would primarily fall on high-income taxpayers because they are more likely to own larger homes and have more mortgage debt. Middle- and lower-income taxpayers would be much less likely to face a tax increase.

Currently, the deduction costs the U.S. Treasury an estimated $63.6 billion a year.

Two primary factors influence how much home mortgage interest is deducted in a state: state housing prices and state income levels. The century-old home mortgage interest deduction is the third largest deduction taken by high-income households.

Bloomberg reports that, without the tax incentives, along with a proposed end to property tax deductions, economists warn that home sales may be hurt in cities where prices are on the rise, from Denver and Portland to Boston and Washington. The National Association of Realtors claims the tax change would cause price declines of about 10 percent nationwide.

At a time when a post-recession downturn in home ownership has the real estate industry worried, some prognosticators say middle-income renters would shun home buying under the proposed tax reforms, especially in high-priced areas.

Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody’s Analytics Inc., said recently that the proposal “is a backdoor way of rendering the mortgage interest deduction close to worthless.”