In this era of emergency managers, the financial struggles of Michigan cities are not an unavoidable trend or an accident of timing – they are based in large part on the state Legislature’s thievery of $7.5 billion in tax revenues that were marked for cities, townships and counties.

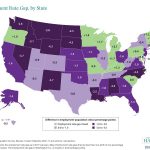

That’s according to a new report by the Michigan Municipal League which found that Michigan ranks last in the nation in state funding for municipalities and is the only state that experienced a decline in local funding from 2002-2012.

In fact, the 49th state, Ohio, has increased total municipal funding by over 25 percent in that 10-year period, according to the MML. The average increase nationwide – in Red States and Blue States — is nearly 50 percent. But Michigan is down almost 9 percent.

During the 10-year period that MML studied, relying upon U.S. Census data the group found that the Legislature, in an unprecedented manner, cut revenue sharing that cities use to pay for fire and police departments, local roads, libraries and parks.

To coincide with the report by the MML, the state’s main advocacy group for cities, Anthony Minghine wrote a pair of guest columns. Minghine, the group’s chief operating officer, essentially argues that the state’s funding system is counterintuitive, counterproductive and simply crushing to towns across the state.

Municipal leaders call it the “Great Revenue Sharing Heist,” as legislators and governors annually tried to shore up the state budget by grabbing hundreds of millions of dollars from the pot of money for local funding.

As Minghine pointed out in a column for the Free Press on Sunday, the lack of state funding leaves cities and townships without a means of making up for the losses:

Think for a moment about how cities generate revenue. Property taxes are a function of two things: millage rate and taxable value. What makes taxable value higher in one community versus another, is in essence, what makes one city or village more desirable than another. Great places command higher prices, which translates into greater taxable value. This in turn generates more revenue. It is simple math.

When an emergency manager balances the books by closing parks, eliminating programs and services and forgoing investments in infrastructure, he makes it a less desirable place. This of course, diminishes the value of the city and its revenue-generating power. Consequently, the city offers even fewer services, which further diminishes it as a place where people want to live, which diminishes value, and so on. It’s a death spiral — a fundamentally flawed process that will never work given Michigan’s current municipal finance model. The system is broken.

Beyond the cutbacks forced on communities by Lansing, another factor is the inflationary cap placed on residential tax values by Proposal A of 1994. That cap has so handcuffed some cities that will take them another two decades to get their home values back to where they were before the 2007-08 market collapse.

In addition, attempts to attract young college graduates to Michigan cities have mostly failed. At one point, Gov. Jennifer Granholm created a “Cool cities” program. After some time, the list of Michigan “Cool Cities” grew so long that the program practically labeled every city a Cool City. You don’t get to be cool that easily.

In his column for Bridge Magazine on Friday, Minghine made the case that people – professionals, entrepreneurs, small business owners – are attracted to cities that offer a good quality of life.

They expect the basics, such as safe drinking water, and they want a few amenities that make their town enjoyable. In return, the community grows and prospers and becomes fiscally strong:

Few people pick where they want to live because of low taxes.

They pick a place because it offers the things that matter to them. But in Michigan, we remain anchored to a decades-old funding model that does not direct revenue in a way that will invest in the things that really matter. Make no mistake, businesses value talent above all else and if we can attract and retain the talent, the businesses will follow.

The research supports community-based “place-making” strategies as a way to strengthen both our economic and social future. Walkable urban places command a premium of over $20 a square foot, generate 10 times the tax revenue, and maintain higher values during recessionary times. Property values are typically 5 percent higher when homes are located near parks. Investments in the arts create jobs. Transit and “multimodal infrastructure” are correlated with increased jobs and wages. It is time to begin investing in Michigan’s future, and Michigan’s future is in its communities.

Ohio has slashed local funding by 50% but don’t let that get in the way of your bsing