While the Legislature gradually achieved a bipartisan package of asset forfeiture reforms in 2018, police departments across the state continued to aggressively seize property from those accused of drug crimes.

Even as legislation was gaining steam, police departments statewide were engaging in a 15 percent increase in the seizure of assets compared to 2017.

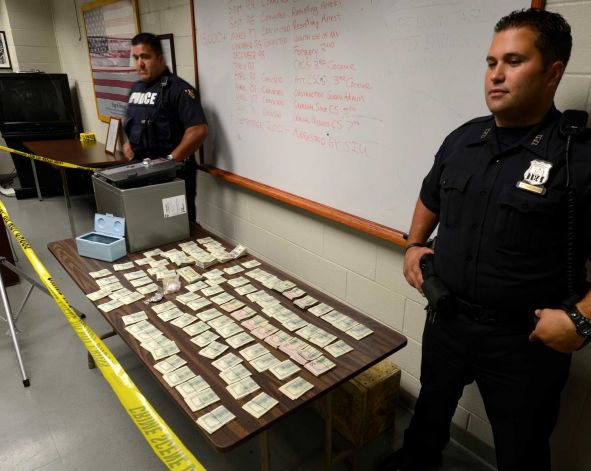

Michigan Capital Confidential reports that over 6,000 persons had more than $15 million worth of property and cash confiscated and kept by Michigan law enforcement agencies in 2018, according to a report released June 30 by the Michigan State Police on the practice of civil asset forfeiture.

Of those targeted by the controversial practice, less than half, 2,810, were convicted of the drug crime for which the property was seized. What’s more, 514 were never charged at all. But the police gained “big money” in the process.

At issue was a way of doing business by the state’s police agencies that allowed them to seize the assets – homes, cars, cash and more — of those arrested on drug charges, well before the defendants were convicted of anything. If property was allegedly gained through illegal drug trafficking, it was fair game for the cops.

In April, the Michigan Legislature enacted long-awaited reforms to the law. Starting in August, the new statute requires a criminal conviction, in all but rare situations, before officials can retain seized assets.

Most of the confiscated property in 2018 was cash, $13.8 million, which was then used by police agencies to supplement their own budgets. As always, marijuana was the big driver of asset forfeiture, not highly addictive drugs that lead to deadly overdoses.

In the state Capitol, police groups lost their lobbying effort to kill the legislation but they succeeded in gaining a significant loophole. The new law still allows cops to seize property worth more than worth more than $50,000 – which would certainly include a home or a couple of cars – to be forfeited even if the owner is not convicted of a crime.

With basic property rights at stake, the standard practices within the civil asset forfeiture process were so egregious that the left-wing and the right-wing of Michigan’s political spectrum teamed up several years ago to put an end to the system, which critics called “legalized larceny” by law enforcement. The American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan partnered with the Midland-base Mackinac Center for Public Policy.

Asset forfeiture laws have come under fire across the country, with Michigan’s laws rated among the worst by reformers beginning in 2010.

A turning point in Lansing came in 2015 when a self-described soccer mom with four young children outlined for state lawmakers how her home was ransacked by police during a drug raid gone wrong. The narcotics officers, acting on a tip, recklessly assumed everything on the premises was paid for by drug sales.

Annette Shattuck, a medical marijuana patient, recalled the raid by the St. Clair County Drug Task Force during a House Judiciary Committee hearing:

“After they breached the door at gunpoint with masks, they proceeded to take every belonging in my house,” Shattuck said. The cops’ haul included bicycles, her husband’s tools, a lawn mower, a weed whacker, televisions, her children’s Christmas presents, $85 in cash taken from her daughter’s birthday cards, the kids’ car seats and soccer equipment, and vital documents, such as driver licenses, insurance cards, and birth certificates.

“How do you explain to your kids when they come home and everything is gone?” she said at the time.

The police even confiscated a sex toy, Shattuck’s vibrator. The drug trafficking charges were subsequently dropped, leaving Shattuck and her husband to undertake the arduous and expensive legal process of reclaiming their property.

Jarrett Skorup of the Midland-based Mackinac Center, who has written numerous times on asset forfeiture, said instances are common in which the target of forfeiture was not a drug kingpin. Instead, it was a low-income petty drug user whose low-value vehicle was taken by police.

In June, the Institute for Justice, a national advocacy group for forfeiture reform, released a study that found asset forfeitures have a minimal impact as a crime deterrent and that forfeitures are most aggressively used by police in communities with budget problems due to financial distress.