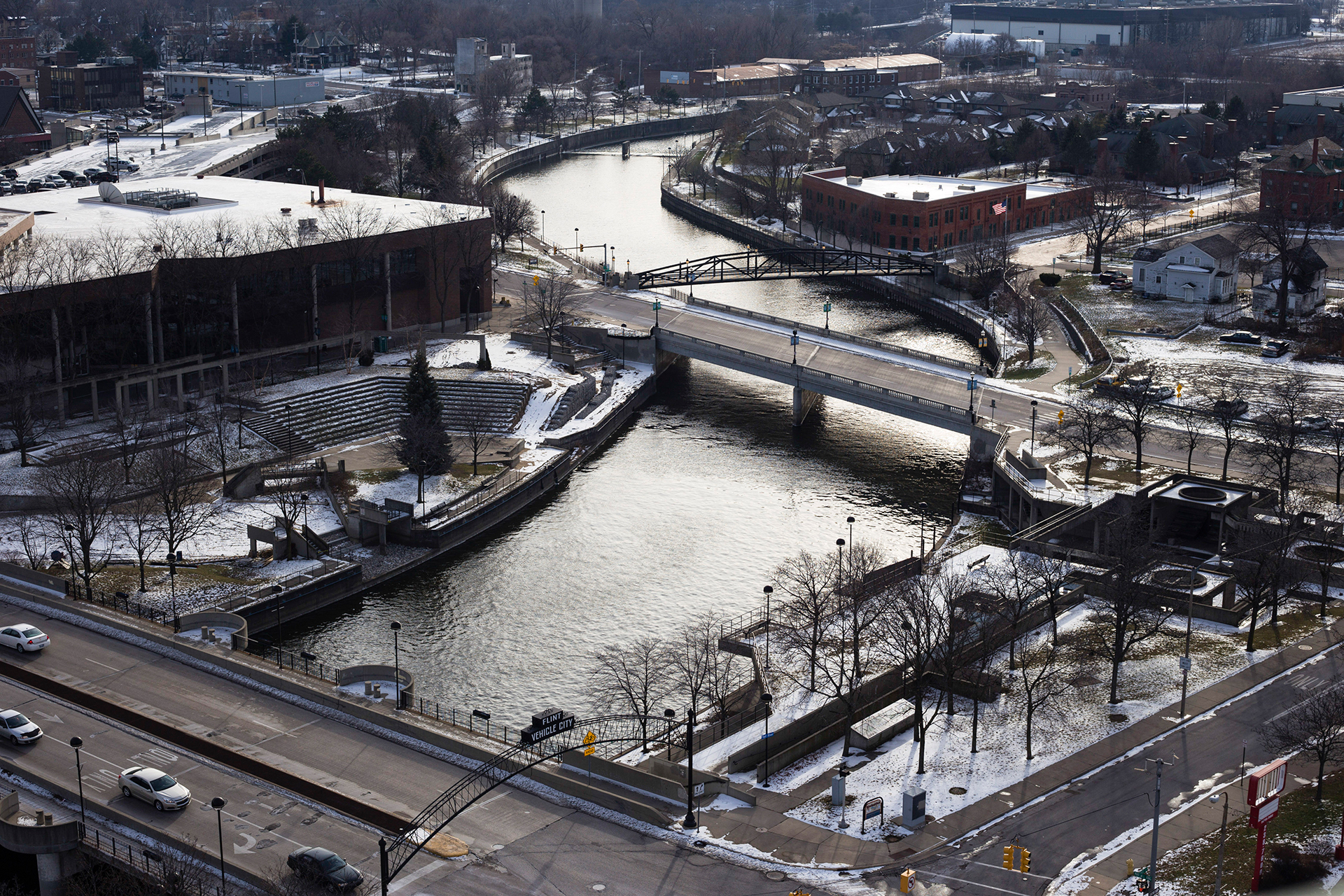

As Flint awaits the arrival of federal funding to remove lead-tainted water pipes and anticipates additional help from the state, city officials received bittersweet news this week as the Department of Natural Resources tentatively awarded $6 million for a beautification project along the banks of the Flint River.

The DNR announced that Flint is in line to receive funding for the purchase of 60 acres along one mile of riverfront to develop a park on a former factory site known as Chevy Commons . The rejuvenation project will be financed by the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund, a dedicated pot of money that annually finances recreation projects based on applications made by the counties.

According to the DNR, which oversees the process, the allocation to Genesee County for the Flint River waterfront will “contribute to additional water-based recreation opportunities, improve community connectivity with regional trails and to natural resources, allow for ecosystem restoration on a (former) industrial site, improve storm water and flood control, and spur additional riverfront development.”

Sounds nice. But I’m not so sure how many Flint residents who have endured years of hardship due to the lead contamination in their drinking water will want to enjoy a sunny summer afternoon at the banks of the polluted Flint River, which has become the symbol of this city’s internationally recognized crisis.

To be fair, the grant money is not a diversion of funds for pipes and public health, as the trust fund money is restricted by law. But the irony is thick, as the feds still have not provided Flint funding and earlier this month, after numerous delays on Capitol Hill, it seemed Congress might adjourn for the year without taking action.

Early this morning, the Senate approved the $170 million package for Flint and other communities that the House finally passed on Thursday.

If, as expected, President Obama signs the legislation, Flint would receive $100 million in grants to replace lead service pipes, but not until state officials submit a plan of action to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for approval.

The legislation also gives Michigan the legal authority to forgive $20 million that Flint owes to the state for outstanding loans for water infrastructure improvements.

In addition, Flint could apply for a portion of $200 million in federal low-interest loans for communities suffering from water contamination.

Congressman Dan Kildee, D-Flint Township, said “the next step clearly falls to the State of Michigan.”

“They have been silent for many, many months. I don’t believe they can take the position that they’ve sort of checked the box and they’re done. Flint needs a lot more help,” Kildee told The Detroit News.

Flint Mayor Karen Weaver announced last week that a new University of Michigan study found that the city’s water system problems may be far worse than previously anticipated. As many as 29,100 Flint residences have lead or galvanized steel service lines that need to be replaced, at team of U-M professors concluded, nearly the amount estimated when the city’s pipe replacement program began in February.

The number is nearly twice the 15,000 the mayor estimated would need replacing when she kicked off her FAST Start pipe replacement program in February.

The mayor’s goal is to replace service lines for 1,000 homes by the end of the year, weather permitting. The number of homes that will receive new pipes next year depends on the funding received.

Meanwhile, in Lansing the $47.6 million worth of state trust fund projects for 2017 was applauded by Gov. Rick Snyder.

“These recommendations reflect (an) ongoing commitment to a better quality of life for Michigan citizens in every part of our state,” Snyder said.

The board’s final recommendations will go to the state Legislature for review as part of the appropriations process. Upon approval, which is typically routine, the Legislature will forward legislation to the governor for his signature.