Gov. Rick Snyder devised a strategy to talk tough about the Enbridge oil pipeline in the Mackinac Straits while his administration and the state’s consultants on the environmental issue worked with the Canadian company to put the best face forward on a bad situation.

That’s the bottom line from an extensive piece of investigative journalism produced by Bridge Magazine and the Michigan Campaign Finance Network (MCFN).

Michigan leaders have allowed lobbyists and officials with direct relationships to Enbridge offer extensive input about the fate of the company’s pipeline even as the Snyder administration has claimed that a crackdown, aimed at protecting the Great Lakes environment, is in the works.

The Bridge/MCFN investigation was based in large part on a review of more than 5,700 documents, including public disclosures and internal emails obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. Bridge and MCFN also interviewed more than a dozen experts, state officials and former state employees.

The documents showed a high-ranking state official allowing an Enbridge lobbyist to get a preview of an upcoming announcement about tougher standards for the pipeline, and internal Snyder administration “talking points,” before the supposed clampdown on the oil company was made public.

The investigation also found that earlier this year, a state agency hired the lobbying firm working for Enbridge to provide public relations training for state employees who answer questions from the media about the pipeline. One of the firm’s key employees for the training, according to the contract, had previously worked for the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) but resigned in the wake of the Flint water crisis.

According to Bridge/MCFN, a leader of the PR effort is Brad Wurfel, former spokesman for the DEQ. When the Flint water crisis was first revealed, Wurfel infamously claimed that residents needed to “relax” and that scientists were causing “hysteria.”

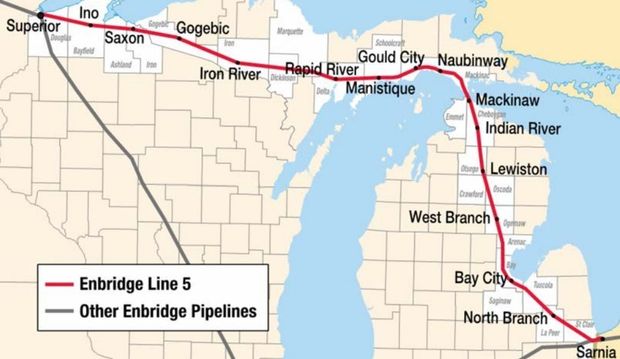

Enbridge Line 5 traverses much of Michigan

Amid growing concerns about the potential of a catastrophic oil spill in the Great Lakes, state officials have tried to outdo each other in publicly denouncing Enbridge’s failure to adequately maintain and protect the Line 5 pipeline from a rupture.

Last year, Snyder announced a deal with Enbridge for a series of new safeguards after it was revealed that Line 5’s underwater protective coating in the Mackinac Straits was damaged in several places.

The November deal required Enbridge to study alternatives to Line 5, improve underwater monitoring in the Straits, swap a Line 5 segment beneath the St. Clair River for a tunnel-protected line, and study ways to bolster safety at other water crossings.

“Business as usual by Enbridge is not acceptable and we are going to ensure the highest level of environmental safety standards,” Snyder said in a press release.

However, the state gave Enbridge an early glimpse at its strategy for selling the deal to the public, emails show. The state shared its talking points, a question-and-answer document and a list of media members who would take part in a press call about the new developments.

Enbridge lobbyist Deborah Muchmore was provided a press release about the reforms before it was made public, giving her the opportunity to suggest revisions.

Yet, the state Pipeline Safety Advisory Board members at the center of the supposed crackdown on Enbridge were kept in the dark about the details.

The Pipeline Safety Advisory Board was not given the opportunity to work with the Snyder administration on the Enbridge pact, and the coordination of the public messaging represents a big concern, said Mike Shriberg, executive director of the National Wildlife Federation Great Lakes Regional Center and a member of the advisory board.

“They are clearly looking out for the interests of Enbridge,” he told Bridge/MCFN.

But Shriberg said he gives the state “a pass” on some dual connections among those analyzing Line 5 for the state who also have worked on a contract basis for Enbridge.

For example, one of the most respected Great Lakes water quality experts in Michigan, Guy Meadows of Michigan Technological University, previously served on the advisory board but has also served as the lead analyst on three research projects funded by Enbridge. After Michigan Tech received a $750,000 state contract, Meadows is now completing a risk-analysis of the state’s oil and gas pipelines.

Schriberg offered this ominous warning:

It’s difficult, he said, to find independent experts without some connection to Enbridge, which says it operates the “world’s longest and most complex crude oil and liquids transportation system.”