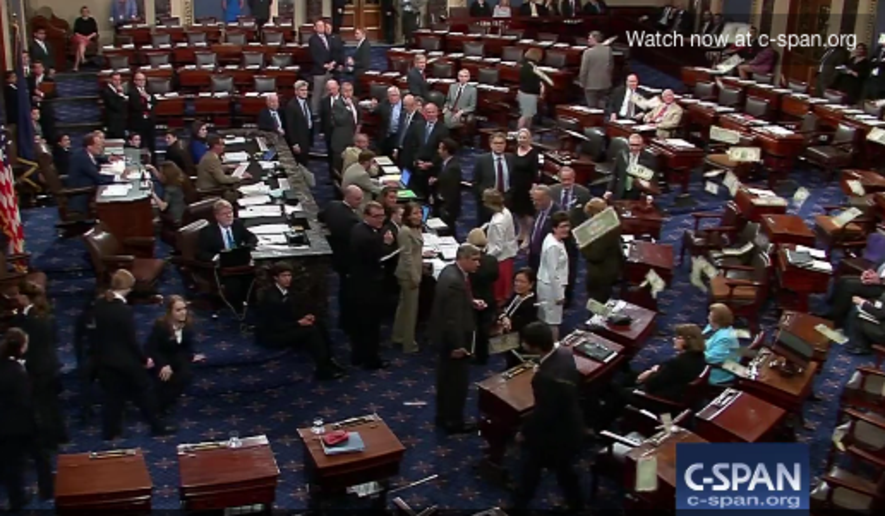

President Trump has again introduced the idea of ending the filibuster rule that requires a 60-vote supermajority in the Senate when a contentious issue arises.

Traditional thought is that the filibuster requires a 100-member Senate that acts incrementally, in moderation, and against any sudden swings in public opinion. The House, with 435 members acting upon the whims of tiny slices of America, governs by a simple majority.

When Trump signed a controversial 2,300 page, $1.3 trillion spending bill last month, he proclaimed that he would never again sign such a far-reaching piece of legislation, and he asserted that the messy budget process signals the need to end the filibuster and impose a simple 51-vote majority in the Senate on all matters.

Some conservative Republicans are so dismayed by this all-encompassing omnibus bill, a tit-for-tat increase in spending on favorite projects by the Senate GOP and Democrats to break a logjam, that they are raising the prospect of a new process on Capitol Hill for approving federal budgets.

After all, the GOP has held control of the House and Senate for more than seven years, yet the Republicans have failed to avoid countless stopgap measures, whether through continuing resolutions or foolish government shutdowns.

A northern Michigan GOP political consultant, Dennis Lennox, proposed in an Op-Ed column for The Washington Examiner that congressional Republicans seeking a solution should take a look backward. To end the dysfunction and gridlock in the Republican Congress on fiscal matters, Lennox suggests that the GOP should start with an American version of the British Parliament Act of 1911.

While that might seem an obscure reference, some symmetry suggests history might prevail.

The Parliament Act harkens back to a time when the U.S. and the UK each had a popularly elected lower house in the legislative branch of government and a higher chamber that was unelected. The Parliament Act broke precedent by allowing the elected British House of Commons to overrule the unelected House of Lords on budget bills. Two years later, the 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ended the process of state legislatures selecting U.S. senators and instead imposed elections by popular vote on a broad, statewide basis.

Lennox lays out his case this way:

What is needed most is a legislative mechanism to resolve the

deadlock caused by a Senate that rejects, delays, obstructs, or

otherwise fails to consider bills duly passed by the House.As a conservative, I am inclined to oppose reform simply for the sake

of reform. However, it is clear that only something as radical as the

Parliament Act could end the dysfunction in Congress: The House needs

a way to overrule a Senate that doesn’t act on or rejects budget bills

that have passed the House. That might mean the House can pass a

budget or appropriations bill if the Senate hasn’t acted in a given

period of time (perhaps three months). Alternatively, perhaps a

super-majority of the House could vote to send a budget or

appropriations bill straight to the president’s desk, without any

Senate action.The Founding Fathers recognized the legitimacy of the popularly

elected House of Representatives, as the Constitution requires budget

bills to originate in the lower house. Yet for years the

Republican-controlled House has passed budget bills only for them to

die in the Senate, where minority Democrats can obstruct and block the

GOP from enacting the political program that gave them a majority at

the ballot box. (The dysfunction is only worse when a different party

controls each house.)

Any attempt to impose this type of unorthodox authority within the legislative branch would spark a political battle, likely along constitutional grounds, but it is interesting that such an idea is floated in this era of defective congressional functioning.