As proposed work requirements for Medicaid recipients take shape as a major campaign issue in the upcoming state elections, Michigan has taken a place in the national spotlight as the work rules seem to target inner-city minorities while exempting northern Michigan’s white, rural areas.

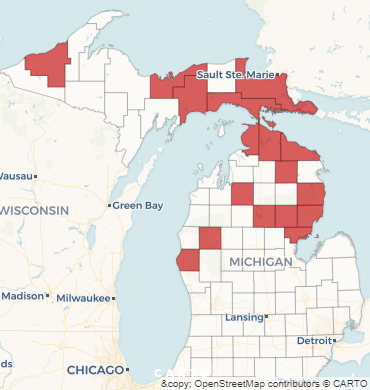

Because the Republican legislation approved by the state Senate exempts counties — but not cities — with high unemployment rates, the bill as currently written would allow Up North folks to continue receiving Medicaid coverage while urban blacks would be kicked off the rolls. Some 17 northern counties would be excused due to economic hardship while cities with rampant joblessness and significant African American populations, such as Detroit, Flint, Saginaw and Muskegon, would not receive a break from the work rules.

Some critics of the legislation now pending in the state House say that the unequal treatment could violate the 1964 federal Civil Rights Act. Others claim that, beyond the racial overtones, the bill carries partisan motivations as the northern areas that would not be affected lie within solidly Republican territory.

With reporting by Bridge Magazine leading the way, news stories about the controversial Michigan proposal have been published by the New York Times, The Washington Post, Vox, New York Magazine and the Huffington Post.

Rural residents get a break, city residents do not

The metric that would trigger an exemption is a Michigan county with an unemployment rate of 8.5 percent or more. But Bridge found that the 17 counties that meet that standard (outlined in the map above), with a combined population of 303,000 people, are 89 percent white. Every county is represented by a Republican state senator.

In contrast, six cities with a combined populace of 894,000 people – 72 percent black – have an unemployment rate of 9 percent or more but they are located in counties that fall below the 8.5 percent threshold. All but two of those counties are represented by Democratic state senators.

So, the legislation distinguishes between cities and counties in a way that draws suspicions. Senate Republican leaders adamantly deny that race played any role in choosing the work standards.

At issue is the concept that work requirements attached to “safety net” programs for poor and low-income households should not apply in high unemployment areas where jobs are hard to find. That precept extends back more than 20 years to the wide-ranging welfare reforms of the 1990s approved by Congress and signed into law by President Bill Clinton.

Earlier this year, President Trump revised that model by encouraging states to apply for federal provisions that would allow fairly strict work requirements for recipients of food stamps, Medicaid or subsidized housing.

Most of those in Michigan who rely on Medicaid coverage for healthcare consist of senior citizens, the disabled or chronically ill, and poor children. They would automatically receive an exemption. Among the rest, about 70 percent work, even if their hours and wages are minimal.

An estimated 300,000 recipients could lose their Medicaid benefits if they do not adhere to the weekly mandate of 29 hours of work, education or job training. The savings for taxpayers due to the work rules would be minimal as the legislation would require a costly bureaucratic system to enforce compliance.

But the county vs. city debate is an issue that is more complicated than it may seem.

Transportation to jobs becomes an issue

In recent interviews, state Sen. Mike Shirkey (R-Clarklake), the sponsor of the legislation, has said that proximity to jobs is key when deciding who deserves continued Medicaid coverage.

“I don’t know why anybody in Flint would say (they) need to be treated separate than Genesee County,” Shirkey said. “I mean, is it too much of an expectation to look for jobs, if you happen to live in Flint, to look for a job in Genesee County? And the same argument applies to Detroit and Wayne County. How granular do you want to get?”

In another interview, Shirkey asserted that rural residents in northern Michigan deserve more leeway in finding a job than people in places like Detroit or Flint. Rural residents, he argued, lack public transportation and have to travel farther for work.

“The lower the population, the fewer the jobs. And the lower the population, the greater the distances to the jobs,” he said. “I’ll say that the public transportation system in Southeast Michigan is not as good as it should be, but it’s basically nonexistent in the rest of the state.”

Shirkey

Opponents of the legislation maintain that Shirkey fails to understand that urban residents are less likely to own a car than people in rural areas. City dwellers, particularly in Detroit, face steep auto insurance rates that deter car ownership, and a transit system that puts jobs in far-flung suburbs that often aren’t served by buses.

As for the overall impact, the 17 northern Michigan counties that would be exempt have a combined population of less than half the population of Detroit alone.

Of course, one unspoken issue in this debate is the irrationality of the Medicaid “cliff.” Under the expanded Medicaid services created by the Obamacare program, income eligibility is modestly set at $16,000 for a single person, ranging up to $33,000 for a family of four. But Medicaid offers no phaseouts, so the first dollar earned above those income limits results in the cancellation of Medicaid coverage.

That presents a dramatic incentive not to work more hours or earn more income. In contrast, the food stamp program, known as SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, works on a graduated scale. Once recipients reach a certain threshold, perhaps due to a new job, as their income rises the amount of their food benefits declines.

Meekhof

Meanwhile, Republican Gov. Rick Snyder continues to balk at the work requirements bill and, due to a likely gubernatorial veto under current circumstances, the House is in no hurry to send legislation to the governor’s desk.

State Senate Majority Leader Arlan Meekhof (R-West Olive) told the Times: “The bill is in the early stages of the legislative process and will likely see changes and revisions before it makes its way to the governor.”

Snyder spokesman Ari Adler told Bridge: “The county unemployment rate exemption is just one of a host of issues the governor will continue to work on with Sen. Shirkey as we continue our dialogue on the bill.”

Map: Bridge Magazine