With a home construction market that is seriously out of whack, every Michigan county now has a significant problem with a lack of affordable housing for low-income households and the working poor.

According to new research, the only area of the state where a substantial amount of low-income housing is available is at the tip of the Thumb area, in Tuscola County. In urban areas and across southeast Michigan, the problem is particularly acute.

The nonprofit Urban Institute took a look at how many affordable housing units are available in Michigan for extremely low income (ELI) families – those earning 30 percent or less of the local median income, about $15,000. Only Tuscola offered more than 80 low-priced units per every 100 ELI families.

In many of Michigan’s largest counties, the number of financially viable apartments or other rental options stands at less than 40 units per 100 ELI families. Those areas (as identified on the Institute’s interactive map) comprise a wide swath across the southern half of the Lower Peninsula, including Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, Washtenaw, Ingham, Kalamazoo and Kent counties.

In this case, “affordable” means a monthly rent that eats up no more than 30 percent of a family’s household budget.

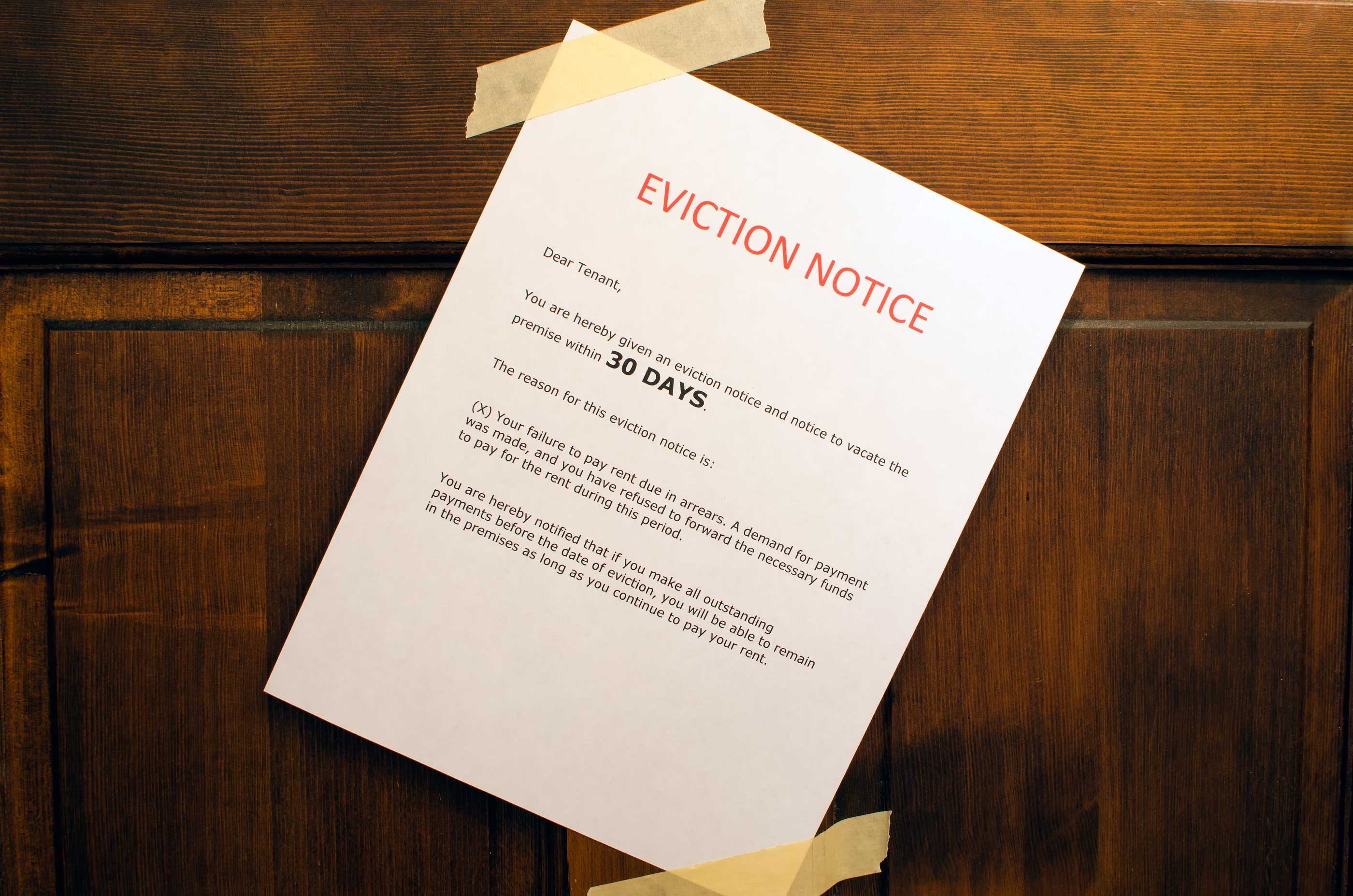

That means that the poorest of the poor are scrimping on food, utilities and other basics, such as gasoline or medical care, to avoid eviction and possibly homelessness. In addition, those that receive federal housing subsidies now face the prospect of the Trump administration cutting their allotment at a time when the housing shortage is reaching a critical phase.

To be clear, this is a wage issue, not just a rental-rate issue. And it affects single-parent families, displaced workers and Millennials trying to gain their footing following college graduation.

As a result, existing starter homes and “fixer-uppers” that go on the market with inflated price tags are snatched up within days, even hours, across Michigan and the U.S.

The Michigan numbers for housing availability are part of a larger study that offers this stunning conclusion: Every county in America has an affordable housing problem. The Urban Institute reports that the shortage extends from coast to coast and throughout the Midwest, even affecting small cities and rural areas:

In some small towns, rising rents are making the affordability crisis worse. Small resort towns, like Breckenridge, Colorado, and Traverse City, Michigan, are feeling the squeeze of gentrification. Tourism fuels the economy, opening up jobs for locals and seasonal workers, but affordable rentals are hard to find. And many landlords can earn more from short-term rentals to tourists than long-term leases to residents.

At the same time, the Trump administration’s proposed legislation would raise rents on more than 4 million low-income households, a savings of $3.2 billion a year for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The plan would reduce rental assistance in a variety of ways and would raise minimum out-of-pocket housing payments for households with relatively high expenses, such as for medical costs or child care.

In Michigan, most of those who would be affected — about 180,000 — are seniors, the disabled or children, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. The average rental increase would amount to $720 a year.

In Detroit, officials concerned about the gentrifying effects of a new population influx in the downtown and Midtown areas are hoping that federal assistance will continue on a wider scale. In March, Mayor Mike Duggan unveiled plans to establish a $250-million affordable housing fund that will preserve 10,000 existing units in neighborhoods throughout the city and develop 2,000 new units within the next five years.

It’s in the rapidly growing cities across the American West, where housing demand is high, that the affordability problem can be best explained. The Urban Institute took a closer look at the economic forces resulting in housing shortages by focusing on the construction patterns in the Denver area, which has a strong residential building market.

The Washington Post reports what the Institute researchers found:

For renters who make 30 percent of the local median income, or even 60 percent, new multifamily buildings were simply impossible to build without public help once you factor in the costs of acquiring land, paying designers, constructing buildings, maintaining them and servicing loans.

… Nudge down the design and development fees, pay the construction workers less, drop the interest rate as low as it will go, spend nothing on maintenance, even assume that someone gave the land for free — and the buildings still aren’t feasible. A 50-unit apartment (complex) is still millions short.

… In the Urban Institute’s model, there are really only three ways to solve the equation. You can demand renters pay more than what’s considered affordable to them — 30 percent of their income in rent. Push that assumption closer to 100 percent — assuming the poor don’t need much for groceries, or bus tickets, or school clothes or prescriptions –and you may get there. Or you can push the target income for the renters higher, designing a building for families at 80 or 120 percent of the median income — and that may do the trick, too. But then you’re not really building affordable housing for the poor.

Or you can bridge the gap with public subsidies. That’s the bottom line.