The freedom of the individual worker is winning at the expense of democracy in the workplace.

That seems to be the bottom line after the Supreme Court on Wednesday ruled that state and local government employees who work in an agency that is unionized are free to avoid paying union dues. The decision serves as a major blow to the labor movement at a time when union membership has plummeted in the private sector and may now slide in the public sector.

What’s more, the ruling may open the door to further erosion of labor’s clout as the justices embraced the fairly obscure concept of the “right to silence” for each worker.

One shining feature of unionization has always been the democracy it brings to the workplace. Workers vote on whether to join a union, they vote on the leadership of their union, and they vote on whether to accept labor agreements that those leaders produce through the negotiating process.

But this on-the-job democracy breaks down rather quickly if workers don’t have to abide by the majority outcome of these elections. If a significant percentage of workers refuse to pay union dues, while still expecting all the benefits of union contracts, the democratic aspects of the system are undermined.

The SCOTUS opinion in the case known as Janus vs. AFSCME could invalidate laws in more than 20 states. In Michigan, it will likely remove the requirement that police and firefighters pay dues to their unions.

Funding for politics was not the issue

For 40 years, a Supreme Court precedent stood that said public sector employees do not have to pay for their union’s political activities, but they do have to contribute dues for the costs of collective bargaining and workplace activities related to enforcement of labor contracts.

For 30 years, various court rulings have established the legal standard that private sector workers who pay union dues can opt-out, in various ways, from the portion of those dues that are used for political purposes. Anti-union groups have continued pushing, going beyond the idea that, for example, a worker who is a Republican cannot be forced to pay for the union’s financial support of Democratic candidates.

With Wednesday’s decision, these conservative groups got their wish, as a 5-4 SCOTUS majority ruled all dues paid by government workers are political in nature.

The court tilted the scales significantly by relying on that First Amendment concept known as the “right to silence.” According to Robert Sedler, a law professor at Wayne State University, the majority opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, may have far-reaching consequences. In a guest column published by The Conversation today, professor Sedler wrote this:

The “right of silence” is the guarantee that people cannot be forced to be associated with an idea they do not believe.

… The court held that when it came to public employee unions, all collective bargaining involved ideological and public policy considerations. For government workers, the court said, issues like salaries, pensions and benefits are inherently political. And some employees may not agree with the union’s position on those matters.

For example, if a teacher’s union sought higher wages and benefits for its members, this might result in higher taxes for residents of the school district. And if that position was shared by certain union members, the union would be, effectively, putting words they didn’t believe in their mouth. So, the court said that compelling objecting employees to pay an agency fee (union dues) violated their First Amendment right of silence.

Take a moment and try to get your head around that interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. Elections have consequences – except for workplace elections related to union matters.

SCOTUS is OK with freeloaders

One of organized labor’s strongest arguments against right to work laws, which are essentially at the heart of the Janus case, is that allowing workers to enjoy all the benefits of union representation without paying for them amounts to a “freeloader” clause. In the more genteel parlance of the legal community, these folks who refuse to pay are called “free riders.”

But SCOTUS’ ruling on Wednesday shredded the free rider argument without pause.

In contrast to federal labor law dating back several decades, the high court majority concluded that free riders are employees who are “compelled to take a ride that they did not want,” according to Sedler. “And above all, public employee unions did not need agency fees (dues) in order to effectively perform their role of representing the members of the bargaining unit.”

No need for dues. That assertion surely strikes at the heart of labor leaders everywhere. The court referred specifically to government workplaces where issues at the bargaining table are limited, as pay and benefits are much more regimented due to dozens of worker classifications, plus other factors entailed in a nonprofit operation.

Slippery slope lies ahead

Yet, those well-funded organizations across the country seeking to further undermine collective bargaining must be delighted as they imagine the slippery slope that may lie ahead.

The court precedent could lead to a series of steps by anti-union forces that further degrade the democratic process of unionization in the public sector — and the private sector. The ruling in the Janus case might turn local labor leaders, such as union stewards and unit presidents, into mere workplace activists, seeking to maintain some semblance of a bargaining process without the funding or the personnel to get the job done.

It’s not easy maintaining a fair fight with a powerful corporation if you do not have the finances for full-time union representatives, attorneys, arbitrators and consultants. In order to maintain leverage, a union’s cash reserves are especially crucial at times of a lock out, a walk out or a full-blown strike.

In addition, imagine the difficulties labor could face when recruiting new union workers if the SCOTUS view of free riders becomes widespread. Who wants to vote for joining a union if you’re not sure who will actually contribute to the cause?

All of this comes as union membership nationwide stands at just 10.7 percent, down by approximately half since 1983, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Most of that support shows up in the public sector, 34.4 percent, while the private sector unionization rate is down to 6.5 percent.

The majority of states, 28, now have right to work laws that allow free riders. Michigan, the birthplace of the United Auto Workers, saw a right to work law put into effect by the Legislature six years ago and talk of repeal has faded. Just one-fifth of Michigan manufacturing workers belong to a union.

Scary scenarios to consider

It’s true that union membership is holding steady in Michigan and nationwide. In fact, a tiny increase of 262,000 union workers in the U.S. was recorded in 2017 compared to the previous year. But labor still battles against the political forces that have created a national image problem. The Pew Research Center reported that since 2007, public approval for unions has plummeted, so that less than half the country now has a favorable opinion of them.

The future does not look bright for a movement that played such a pivotal role in creating America’s 20th Century middle class.

The darkest aspects of what may lie ahead center on the prospect that democracy and majority rule slips away bit by bit in the manner that the federal government functions.

It’s not a far reach to suggest an analogy in which the right-wing conservatives’ battle against union representation in the workplace gradually bleeds into a new democratic system – in contrast to our heritage as a republic – where voters who oppose certain tax/spending policies enacted by the congressional majority in Washington can opt out of paying taxes for budget items to which they object.

Imagine where that “cafeteria” approach would lead in our highly polarized nation of 2018, with dramatic, partisan conflicts on display daily about what spending practices constitute the basic 21st Century needs of a functioning federal government.

During the tea party uprising of 2009-10, a common anti-tax refrain was: “You have no right to take what I have earned.” Maybe this will be the next mantra: “I’ll take what I want, but I will not pay for anything more.”

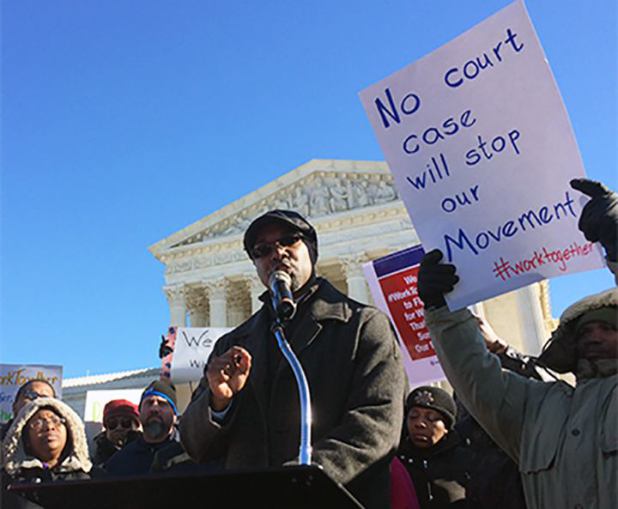

Photo: Workers.org

“ocracy” means “government by”. Democracy – government by the people – is what the founders wanted for our country, despite what Patrick Colbeck thinks. But democracy in the workplace makes no sense, and not having it there is no threat to democratic government. (The biggest threat to democratic government in the U.S. is the Republican Party.)

Collective bargaining is completely unnecessary. The private sector unionization rate is only 6.5%, and the economy is doing fine. Free markets are preferable to allowing the government to set prices, and that includes the price of labor.